Faaslahpal bridges the gap between Islam and Americana by creating scrunchie hijabs for non-hijabi Muslim women.

Faaslahpal.

The name of this startup can be broken down into two Urdu words.

Faslah, meaning distance, and pal, meaning a physical bridge.

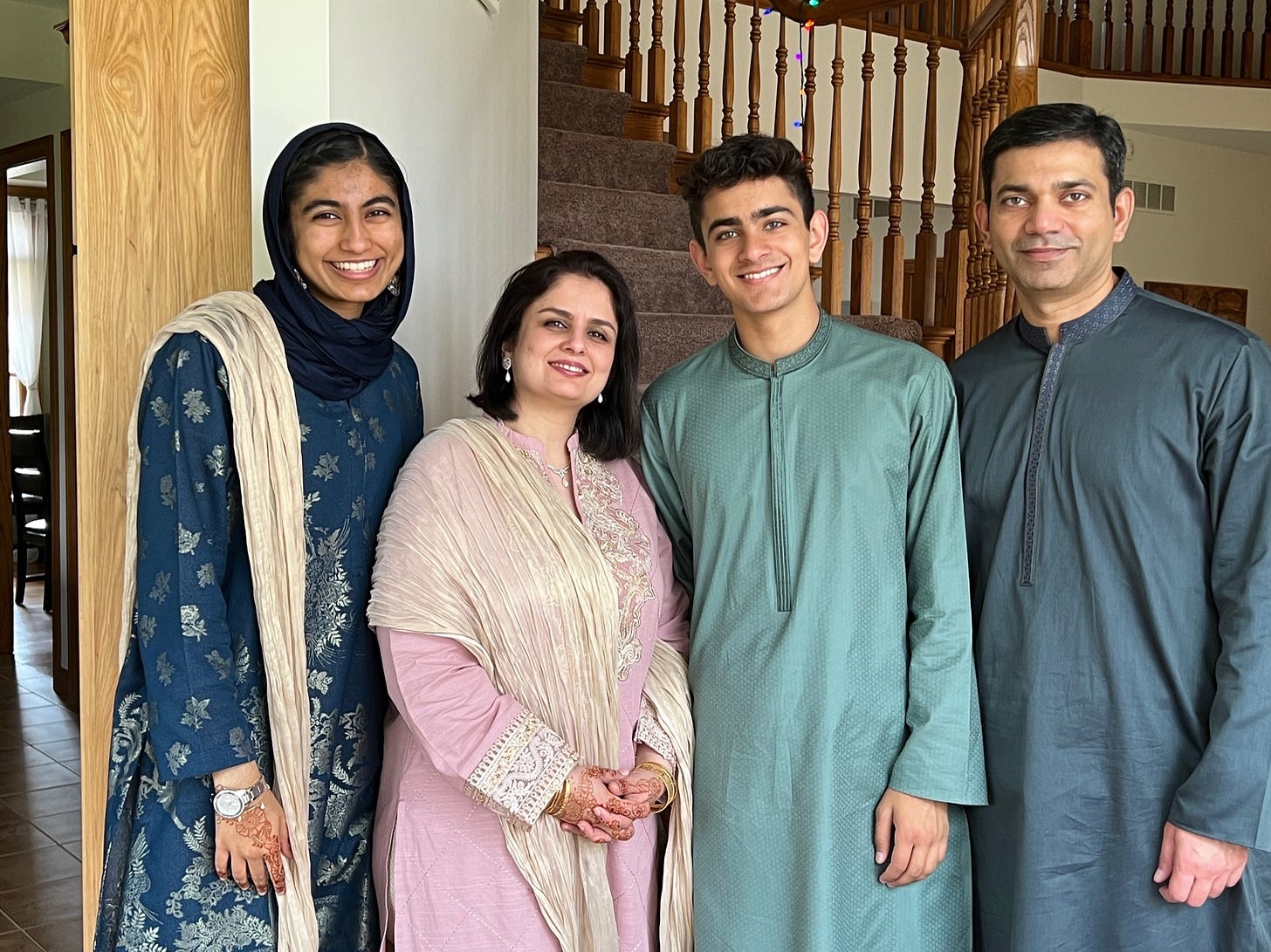

The building of bridges and the connecting of geographies and cultures is the core goal of this iV8 venture, and their mission correlates with the life history of their founder, Aasiyah Adnan. As a first-generation American citizen, she grew up straddling her identities of her Pakistani heritage with her hometown in the midwestern United States. Eventually, upon coming to terms with her spirituality and gaining a sense of inner peace with respect to her cultural identity, she gained the courage to start this company. But her journey begins far before the founding of Faaslahpal and even before she was born, when her parents made the decision to move to America from their home country of Pakistan.

Pakistan

The year was 1991. Adnan Manan was a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed 19-year-old who had just been accepted into the electrical and computer engineering program at Oklahoma State University and was ready to come to the gold mine of job opportunities and education that the US represented. After years of life in his home nest, Manan was ready to head to the States for a high-paying engineering job so that he could provide for his future family—at the dismay of his mother. Of course, the decision was not easy. The warm embrace of family, the weekly reunion feasts, and the place where he grew into his young adult self were unpreferred sacrifices. However, chasing financial security and career fulfillment took precedent, which was only amplified a couple years later when he met his significant other, Saima, whom his family technically arranged him with (although the couple likes to think of it as “a blind date facilitated by relatives”). In any case, Manan made the six-hour flight and endured the much longer immigration process in pursuit of a new life.

He landed with a sense of pragmatic excitement. Here he was at the gates of the country he had dreamed of living in for much of his adolescence. His optimism was hampered, though, by his understanding of the arbitrary nature of the immigration system. Manan had heard of friends and colleagues who had been rejected for no rhyme or reason, so he had the baseline sentiment that getting into the US would be a challenge. His fear only escalated upon entering the long-awaited line to receive his visa.

One of the immigration officers before him was stern and pitiless, handing out denials left and right. Manan was praying to Allah that he would get any one of the other seemingly reasonable officers, but, to his misfortune, he was directed toward The Rejecter. Upon approaching the despot, he told his story of wanting an education in electrical and computer engineering. Today, we might see this as an admirable golden ticket into the nation. In 1991, computers had barely even existed, so Manan’s request perplexed the officer and evoked a look of bewilderment on his face.

Manan was biting his nails in anticipation when the officer spoke the infamous words: “Welcome to unemployment.”

What does that mean, he pondered. Did I get in or not?

Apparently, the officer decided to take a chance on Manan’s dream and allowed him into the country. With a mix of education and luck, he had a chance to prove himself and pursue the aspirations he had always wished for. Years went by, and Manan was summoned back home to Karachi to visit, where his family introduced him to his future wife, Saima, and her family. The pair got along like two peas in a pod, and soon after, Manan’s new wife joined him in America. Together, they decided to settle, for job placement purposes, in the exotic land of Peoria, Illinois, which had developed a very tight-knit Muslim community, giving them a sense of home away from home. A couple of years later, the couple gave birth to their daughter Aasiyah. She was a ray of sunshine and the prize of their extended family as the first grandchild on both of the spouses’ sides. To add to their delight, she would go on to accomplish great things in proliferating the family’s culture.

Peoria

Growing up, Aasiyah celebrated the fact that she was “raised by a village.” Although she was over 7,000 miles from most of her family in Pakistan, she still felt a strong sense of cultural connection to them through the vibrant Muslim community that thrived in her hometown. Sure, her closest relatives were living in Texas and she couldn’t just go to “grandma’s house 40 minutes away” like some of her other friends, but she found other ways to embrace her religion and South Asian values. Being very community-oriented, she frequented dinners at the mosque and went to an Islamic school. One core aspect of her culture that she struggled to accept, however, was hijab.

Aasiyah had never felt pressure from her parents or had direct conversations with them about being a hijabi Muslim woman, although there was a brief time in middle school when she personally considered wearing one. Something inside discouraged her from biting the bullet, though, and it seemed that there was always a reason for her not to wear one. Whether it was her participation in cross country, where wearing a hijab was impractical, or internal strife about how “good of a Muslim” she was, Aasiyah never felt ready to start wearing a hijab regularly.

Her senior year, that mindset began to shift. On one inquisitive run, her blood was flowing and her thoughts were whirring. She realized that she never failed to have a scrunchie on her wrist and that a scrunchie is really just a tube of fabric—just like a hijab. How convenient would it be, she thought, if a scrunchie could be transformed into a hijab so that she could go to prayer at any time without having to prepare herself by carrying around a separate piece of fabric? Creating this could also help make Islam easier to integrate into her lifestyle and usher her toward the Muslim she wanted to be—someone who prayed five times a day.

One late night, Aasiyah decided to whip up a prototype. Basically, the product, which she calls a scrunchie-hijab, is a fat tube of cloth with a sleeve that runs through it so that it can be transformed back and forth between the two. After completing this design, which required her to learn how to use a sewing machine, she felt on top of the world. Not just because she had created something that would allow her to commemorate the inner peace that she was finding in bridging her Islamic and American identities, but because she had created something. Aasiyah had grown up in a household with an engineer for a father and a brother who was very competent in technology, and she grew up being told that she was “not techy enough.”

Creating this scrunchie-hijab, she felt like she had made something that was completely and totally her own. Perhaps this moment is what influenced her to major in bio-engineering at the University of Illinois, with the invigoration of creation being something that gave her a sense of purpose. Besides personal fulfillment, Aasiyah also recognized that what she had made could be a perfect product for any non-hijabi Muslim woman. Whether it was a stepping stone into wearing a hijab full-time, as happened to Aasiyah, or whether it was a convenient way to practice religion at any time, she knew that her idea had the potential to change lives.

Champaign-Urbana

At this point in her life, Aasiyah had entered her freshman year. Although she didn’t necessarily have any concrete plans to turn her scrunchie-hijab into a business, she let the idea ruminate and left open the possibility of doing something with it once she graduated from her bio-engineering degree. Living in the Innovation Living Learning Community (LLC) on campus, however, pulled that intention to the forefront of her mind. At the end of her first semester at the university, she had to present an entrepreneurial or innovative project to the other students living in her dorm. Feeling otherwise uninspired, she and her groupmates decided to run with Aasiyah’s scrunchie-hijab idea. To her surprise, she received positive feedback both from her LLC and the incredibly supportive Muslim community on campus.

Empowered and savvy, she decided to apply for the COZAD New Venture Challenge, under the name of Faaslahpal. She and her team, who interestingly consists of no other Muslim women, were awarded the Orange QC Best Prototype Award ($1000), Grainger College of Engineering AWARE Prize ($1000), and Magelli Office of Experiential Learning at Gies College of Business Prize. But their journey after COZAD was far from over.

One night, Aasiyah was in her room straightening her hair as she was getting ready for a Pakistani fashion show. That’s when she got an email from Manu Edakara, Program Director of iVenture. The message requested her to hop on an impromptu Zoom call, and intrigued by the offer, she accepted. To her pleasant surprise, Edakara told her that he had heard of Faaslahpal and was really interested in what she was doing. However, iVenture is especially interested in startups with a proven history of customer recognition, and he believed that the scrunchie-hijabs were at too early of a stage to benefit from the program. Rather than feeling discouraged, Aasiyah was energized, and Edakara further intrigued her by asking:

“Why haven’t you shown your product? What is stopping you from putting on your prototype right now and walking down the runway at your fashion show tonight?”

That was the night things shifted for her. While she didn’t end up wearing the prototype to the fashion show, she did end up getting down to business. She hunkered down on market research and building awareness for her brand, and she really got in tune with her cultural identity. So much so, in fact, that she started wearing a hijab all the time as an extension of her religion and beliefs. She began to accept that although she may never be a “perfect” Muslim, wearing a hijab or scrunchie-hijab can serve as a reminder for her to always be thinking about her values and the things that are most important to her.

Shortly after coming to this personal acceptance, Aasiyah applied to be a part of iVenture, and two days later, she found out that she got in. Being accepted into the program was a heartwarming validation that the work she was doing was important and impactful, and since starting her work at the accelerator, she has fully adopted the “why not now?” mentality. In fact, the team is on the verge of releasing their very first test launch, where they will be handing out scrunchie-hijabs to people in the community for user feedback. Most importantly, however, they are working tirelessly to unify Muslims in the US and validate their experiences. Aasiyah affirms,

“The real reason why I’m doing all this is because I want to create that community. One of the most core values in Islam is being respectful and caring for your neighbors, and I hope to emulate that through Faaslahpal.”

Although it may be nerve-wracking being a Muslim woman in America in today’s climate, Aasiyah has demonstrated that it can also be gratifying and empowering. Through Faaslahpal, she believes she can help to bridge the American and Muslim identities to build a supportive network of people with shared experiences.

If you’d like to stay up to date on the progress towards this admirable mission, follow Faaslahpal on Instagram or LinkedIn!